Table of Contents

ToggleThe Geological Story of Malta

How the Islands Formed and Their Ancient Continental Connections

Introduction

Malta, a small archipelago in the central Mediterranean, holds a geological history far larger than its physical size. Its dramatic cliffs, fossil rich rocks and distinctive limestone landscapes are the visible traces of millions of years of shifting seas and moving continents. Although Malta stands isolated today, evidence reveals that it was once attached to a much larger landmass. By exploring its formation and its ancient ties to continental structures, we gain insight into the dynamic processes that shaped not only Malta but the entire Mediterranean region.

The Tectonic Setting of the Mediterranean

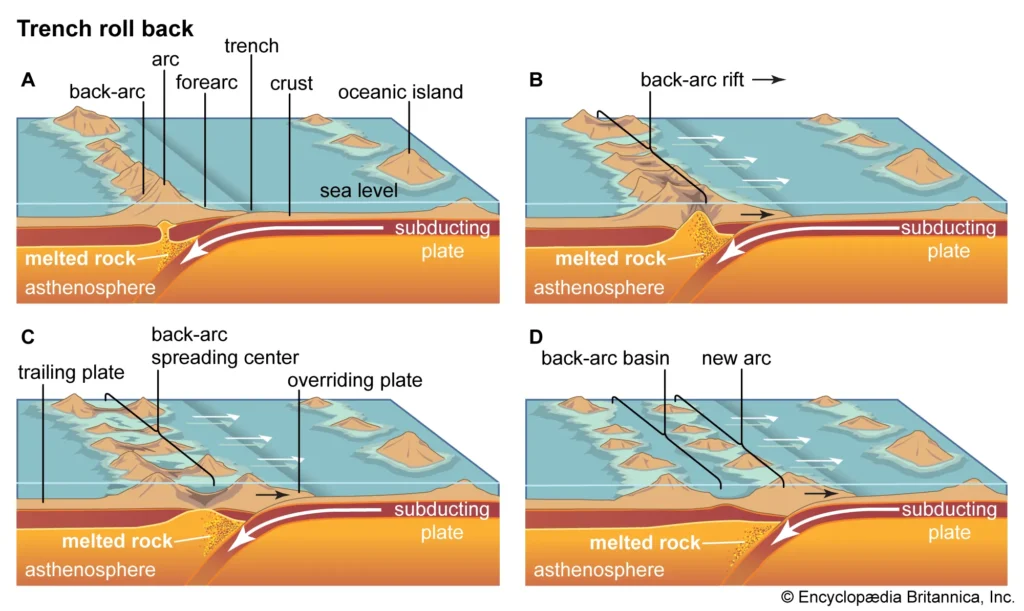

To understand how Malta formed, we first look at the broader geological context. The Mediterranean basin sits at the boundary between the African Plate and the Eurasian Plate. These two massive tectonic plates have been converging for tens of millions of years. Their collision created mountain chains such as the Alps, the Apennines and the Atlas Mountains. This same tectonic movement is responsible for the subsidence and uplift that shaped the sea floor and the islands scattered across the region.

Malta lies on a submerged portion of the African Plate known as the Malta Plateau. This plateau is part of the larger continental shelf that once extended far closer to southern Europe before tectonic forces reshaped the basin.

Malta’s Birth Beneath Ancient Seas

The rock foundation of Malta was not formed by volcanic activity but by the slow accumulation of marine sediments. Between roughly 35 and 5 million years ago, the entire area was submerged beneath warm, shallow seas. Countless tiny organisms such as plankton and corals lived and died in these waters. Their skeletal remains gradually accumulated on the sea floor, compacting over time into layers of limestone and soft marine clays.

These sedimentary layers form the five main rock formations visible in Malta today. The oldest is the Lower Coralline Limestone, a hard and erosion resistant stone that forms many of the island’s dramatic cliffs. Above it lie the Globigerina Limestone and Blue Clay formations, both softer and more easily shaped by erosion. These layers are topped by the Greensand and Upper Coralline Limestone, which form some of the island’s highest points.

Uplift and the Emergence of the Islands

Malta remained underwater for millions of years until tectonic forces began to lift parts of the surrounding seabed. As the African Plate pushed slowly northward toward Europe, stresses in the crust caused alternating patterns of uplift and subsidence across the region. Some areas were raised above sea level, forming islands such as Malta, Gozo and Comino, while others sank to create deep basins.

This process was gradual, occurring over millions of years. As the layers of limestone rose, erosion began shaping the islands. Rain, waves and wind carved cliffs, valleys and unique coastal features. Fossils embedded in the rocks reveal the types of organisms that once thrived in the ancient seas, offering further proof of the islands’ marine origins.

Malta and the Ancient Land Bridges

Although Malta is entirely surrounded by water today, geological evidence indicates that sea levels were far lower during various ice ages. When vast amounts of water were locked up in glaciers, the Mediterranean Sea shrank significantly. During these low sea level periods, large portions of the Malta Plateau would have been exposed, creating land connections between Malta, Sicily and North Africa.

These land bridges were not permanent. They formed and disappeared repeatedly over hundreds of thousands of years as global climates fluctuated. Fossil evidence from Malta, including remains of dwarf elephants and hippopotamuses, suggests that animals migrated across these land connections. Their presence makes sense only if Malta was once physically connected to the continents surrounding the Mediterranean.

The Messinian Salinity Crisis

One of the most dramatic geological events affecting Malta occurred around 5.9 million years ago during the Messinian Salinity Crisis. At that time, the Mediterranean Sea became partially or completely isolated from the Atlantic Ocean. As evaporation exceeded the inflow of water, the basin dried out extensively, leaving behind thick layers of salt and exposing large areas of land.

During this crisis, Malta and the surrounding plateaus would have been part of a vast dry landscape. When the Atlantic waters finally refilled the basin, the geological structures carved during the dry phase became submerged once again, but traces remain in the rock record.

Malta’s Landscape Today

The present geography of Malta is the final product of its long geological journey. Its cliffs along the west coast show the power of uplift, while its bays and inlets reveal the work of erosion. The islands’ step like terrain reflects the differing hardness of rock layers. The soft Blue Clay erodes easily, creating terraced slopes, while the harder limestone above forms protective caps.

This geological diversity has influenced human settlement, agriculture and architecture. Malta’s famous honey colored buildings owe their beauty to the limestone that accumulated on the sea floor millions of years before humans arrived.

Malta’s formation is a story of ancient seas, shifting plates and dramatic environmental transformations. From its origins as marine sediment on the floor of a warm ocean to its role as a land bridge between continents, the islands carry the imprint of a dynamic geological past. Understanding these processes not only deepens appreciation for Malta’s natural landscapes but also highlights the ever changing nature of Earth itself.