Table of Contents

ToggleMalta’s Independence and Republic

A Journey of Sovereignty

On a tiny archipelago in the heart of the Mediterranean, Malta has always been a crossroads of history. Empires rose and fell on its shores, from the Phoenicians and Romans to the Arabs, the Knights of St. John, and the French. For over 150 years, Malta was part of the British Empire, serving as a crucial naval base and strategic outpost. Yet, the Maltese people longed for more than colonial rule—they aspired to self-determination, dignity, and sovereignty. This aspiration culminated in two monumental milestones: independence in 1964 and the proclamation of the republic in 1974.

These two events not only reshaped Malta’s political destiny but also defined its national identity in the modern era. To understand today’s Malta—a proud member of the European Union, a cultural hub, and a sovereign nation—it is essential to reflect on this transformative decade.

Malta’s Road to Independence

The seeds of independence were sown long before 1964. After World War II, Malta emerged devastated from relentless bombings, having played a critical role in the Allied war effort. The bravery of its people earned the nation the George Cross, a decoration still displayed proudly on Malta’s flag. But while the award symbolized recognition, it did not change the reality that Malta remained a colony under British rule.

The post-war period sparked renewed debates about Malta’s future. Some argued for integration with Britain, while others pressed for full sovereignty. The Labour Party, led by Dom Mintoff, initially pursued closer integration with Britain, believing it would guarantee social and economic stability. However, by the late 1950s, negotiations stalled, and public sentiment began to swing towards outright independence.

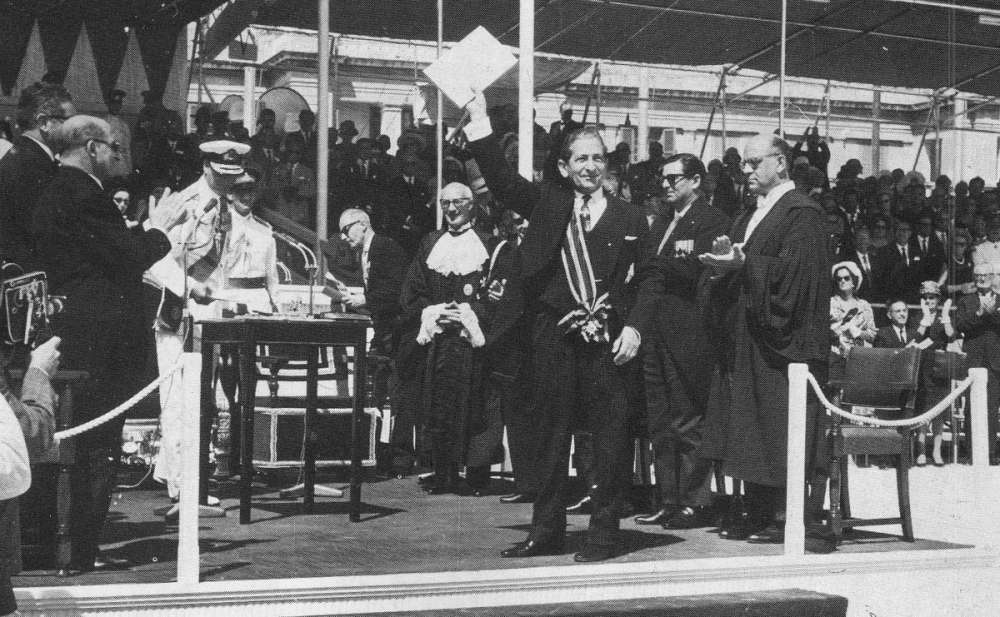

In the early 1960s, under the leadership of Dr. George Borg Olivier and the Nationalist Party, the independence movement gathered momentum. Borg Olivier skillfully negotiated with Britain, emphasizing Malta’s readiness to govern itself. On 21 September 1964, Malta officially gained independence, marking the end of British colonial rule.

The celebrations were both joyous and solemn. A new flag, bearing the George Cross in the corner, was raised, and the Maltese anthem resounded as a sovereign symbol for the first time. Independence did not mean immediate severance from Britain—Malta remained part of the Commonwealth, with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state, represented locally by a Governor-General. Yet, the day represented Malta’s first true step into nationhood.

The First Decade of Independence

The years following independence were critical. Malta had to transition from a colonial outpost to a self-sustaining state. Economically, the island faced major challenges: the British military had long been the backbone of Malta’s economy, and its gradual withdrawal meant Malta had to diversify quickly.

Borg Olivier’s government focused on economic development, education, and strengthening ties with other nations. Malta established diplomatic relations, sought investment, and began building an economy less reliant on British subsidies. The island’s strategic position continued to play a role, but it was now Malta itself, not an empire, deciding how that role would be defined.

Still, the question of Malta’s constitutional structure lingered. Many Maltese felt that true independence required a Maltese head of state, not continued ties to the monarchy. Political debates intensified, with calls for a republic gaining strength.

Becoming a Republic in 1974

By the early 1970s, Malta was under the leadership of Dom Mintoff and the Labour Party. Mintoff, a fiery and determined politician, believed Malta’s independence was incomplete as long as the British monarch remained its head of state. He envisioned a Malta that stood proudly on its own, free from colonial symbols.

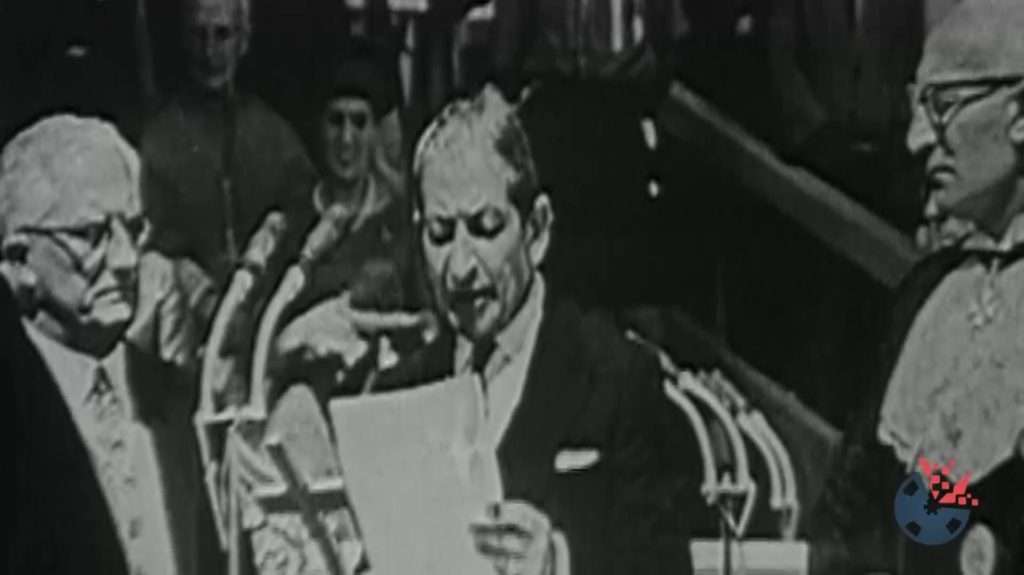

In 1974, after heated parliamentary debates, Malta amended its constitution to establish itself as a republic. On 13 December 1974, the office of Governor-General was replaced by that of a Maltese President, elected by Parliament. Sir Anthony Mamo became Malta’s first President, symbolizing the final break with colonial ties.

This move was more than symbolic—it was a bold statement that Malta was master of its own destiny. While the island remained within the Commonwealth, it was now fully sovereign, with its institutions reflecting its national identity.

The Legacy of Independence and the Republic

The dual milestones of 1964 and 1974 represent the foundation of modern Malta. Independence gave the Maltese people political sovereignty, while the republic affirmed their national pride and identity. Together, they reshaped Malta from a colonial dependency into a modern nation-state.

Today, Malta celebrates two public holidays to commemorate these events:

Independence Day on 21 September, known as Jum l-Indipendenza, which recalls the raising of the Maltese flag in 1964.

Republic Day on 13 December, which honors the moment Malta fully asserted its sovereignty in 1974.

Both occasions are marked with ceremonies, parades, and national pride. They serve as reminders of the resilience and determination of a people who, despite centuries of foreign rule, never lost their identity or sense of belonging.

Malta in the Modern World

Since becoming a republic, Malta has flourished. It joined the European Union in 2004, adopted the euro in 2008, and has become an international hub for tourism, finance, and cultural exchange. The principles of independence and self-determination remain at the heart of its progress.

For Maltese citizens, the legacies of 1964 and 1974 are not distant chapters but living milestones. They are celebrated not only as historical victories but also as affirmations of the values that continue to guide the nation: resilience, unity, and sovereignty.

As the Maltese flag flies proudly over the islands today, it carries with it the echoes of those pivotal years—a testament to the journey from colony to nation, and from monarchy to republic.

Malta’s path to sovereignty is a story of determination, negotiation, and identity. Independence in 1964 ended centuries of colonial rule, giving Malta the freedom to govern itself. A decade later, the proclamation of the republic in 1974 solidified that freedom by ensuring that the head of state was Maltese.

Together, these milestones carved the framework of the Malta we know today: a vibrant, sovereign, and proud nation at the crossroads of the Mediterranean. The journey reminds us that independence is not only about political status—it is about the right of a people to shape their own destiny.